What’s A Khipu?

Introduction

These pages provide a “field-guide” to Inkan Khipu. They allow you to actually view the cords, colors and knots of a sizeable portion of the world’s surviving khipu. Using various computational tools available in this mathematically advanced machine learning age, you can explore with me what khipu are and what could they possibly mean.

Five years in the making, this field guide holds the world’s largest database of well-formed, renderable digital khipu. Sourced from many collections and databases, I am thrilled to unveil these khipus to the world, showcasing the immense efforts of the data gatherers who meticulously measured thousands upon thousands of cords (60,000) and knots (over 120,000). The intricacy of the khipu commands immense respect for their creators, and the preservation of these artifacts by their measurers is even more remarkable. With the aid of high-quality renderings, the circle is now complete, and it’s time to gain a deeper understanding of this fascinating subject!

I think of khipu as an ancient form of “spreadsheet”, made from woven cord. That’s an intentional metaphor - a spreadsheet both calculates (expected) and communicates (unexpected). Most modern khipu scholars agree that khipus serve both purposes, but beyond that, much disagreement exists. Our ability to “read” a khipu has been lost, and khipus remain one of the few remaining ancient communication mediums that remain enigmatic … awaiting full decipherment … Let’s dig in.

Writing with Cloth

Inkan’s were a people constantly on the go. The classic 20th century IBM employee (IBM, the joke went, was short for I’ve Been Moved), would commiserate with a classic Inkan who was always moving around as the Inka rulers sought to expand and control the empire. Consequently life had to be mobile - communication was done by runners, known as chaskis, who could run from camp to camp, carrying information. What was the best available medium to carry information while running? Cloth.

Cloth was viewed as a sacred object - and gifts of cloth, funerals with cloth, etc. show just how much the Inkas’ valued cloth. We forget in this mechanical age how much work goes into a square foot of cloth - the picking of the cotton, or the shearing of the llama, the carding, the spinning, the dying, the weaving. If you’re acquainted with an expert weaver, ask them about Peruvian weaving. Although weaving has been invented 6 times in ancient cultures on different continents, modern weavers marvel at the sophistication, above all, of Peruvian weaving. These are a people, who “got” cloth.

Writing is often regarded as sacred - the word hiero-glyph means sacred writing. It is not a surprise then, that making recordings and communicating knowledge was done with cloth in the hands of a special community of skilled and elite makers known as khipu-kamayuqs who would create, edit, and interpret the khipu. The word khipu-kamay-yoq in Quechua means khipu(knot), kamay(to create), yoq (possessive suffix, here, in context, indicating a permanent possession such as a skill) - i.e. a person who creates knots.

Today, precious few khipu exist. In 1583, at the Third Council of Lima, the Spaniards, banned khipus, and then proceeded to burn all the khipus and kill all the Khipu-Kamayuq’s they could find. The reasons stated were that khipus were religous idolatry and should be banned, but their evidentiary presence in trials, I’m sure was the driving reason. Lest we get too incensed, preceeding Inka conquerors also destroyed the khipus of the vanquished, erasing their accounting memory. The Spaniards went farther and included Khipu-Kamayuqs themselves in the purge. And so was lost the khipu makers’ knowledge and traditions. The few khipu we find today are largely from tombs or in pots from archaelogical digs. Rare earth indeed…

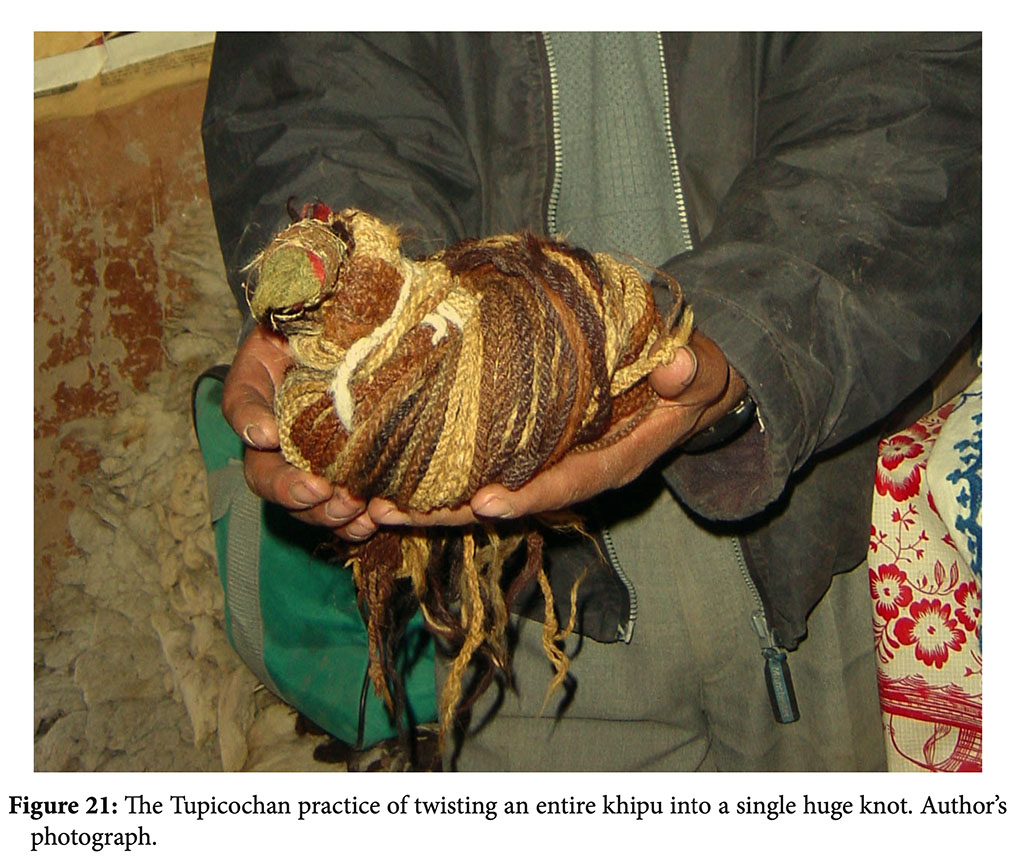

This Khipu Field Guide contains the largest well-formed database of khipu in the world. Currently 654 khipus are drawn and analyzed. More khipu exist to be described, but describing a khipu is a challenging process. Since khipus were meant to be carried, they are sometimes found rolled up like a ball of yarn. The few khipu that have survived to today are ancient - khipus have been found in tombs dating back to 2000 BC. in Peru. The simple act of touching such an ancient khipu can turn the wool or cotton cords to dust. Although the Khipu database has a field for khipu creation date, it is not currently used. Unfortunate. If age was known, it might be possible to simulate “evolution” of khipus to see how they change and become more sophisticated over time.

(Image of rolled-up khipu by Frank Solomon from The Twisted Path of Recall)

An Abbreviated History of Khipu Studies

“The extensive literature of the quipu is of varying value. Some of it is based on actual knowledge, some on inference, some on casual examination of specimens, a great deal of conjecture, and some on pure fabrication.”

L. Leland Locke, April 22, 1920

It was 1923 - the roaring twenties. The opening of King Tutankhamen’s tomb complete with his gold sarcophagus - was THE historical event of the year. Lost however, in the sensational excitement that followed this archaelogical find of the century, was the publication of a little known book, The Ancient Quipu or Peruvian Knot Record by L. Leland Locke. With this magazine sized edition, complete with khipu centerfolds, the modern journey of khipu decipherment was announced to the world. It started not with a bang, but with a whimper.

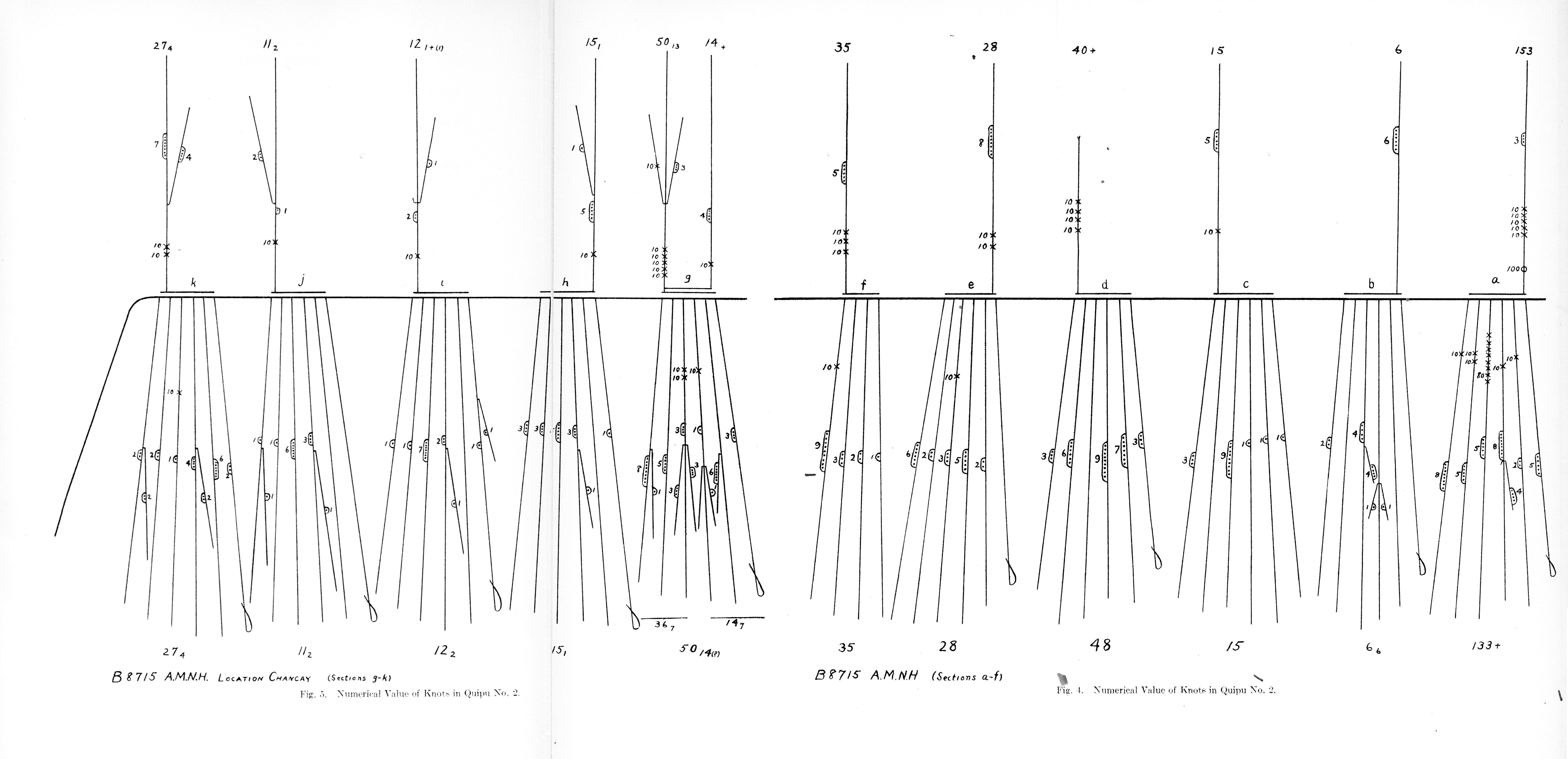

Locke, started teaching mathematics teachers at a Brooklyn college in 1908. Commuting to Manhattan’s American Museum of Natural History for over a decade, he pioneered khipu studies using a database of 42 khipus that he measured and drew. In 1912, Locke published his first paper on his research. The next ten years became an intensive time of annotation and measurement of quipus, with his book being complete by 1920. Through out his life he remained fascinated by computational machines, from the early abacus to modern day mechanical adders and his collection of mechanical computing machines now resides at the Smithsonian. L. Leland Locke’s legacy lives on today - the terms we use today in khipu studies, such as top cords and long knots, are known as the Lockean typology. One hundred years later, I own an original edition of the book Ancient Quipu from 1923. Reading it today, you can readily see Locke was a dedicated and precise man, with a mathematician’s taste for compactness of speech, and a fascination for the mathematics of computation.

What did Locke discover? First of all he discovered that the Inka used base 10 decimal notation. Is that surprising? Yes! When Pizarro conquered the Inka empire in MDXXXII the Spaniards were still using Roman numerals. Have you done subtraction in Roman numerals?

MMXXIII 2023

MDXXXII -1532

——————————————————

= CDXCI 491

Now, CDXCI years later, you can imagine how the Inkas regarded Spanish arithmetic! Vice-versa, you can imagine the astonishment the Spaniards had at how quickly the Inka could do arithmetic using an abacus like device made of a gridded tablet and stones called a yupana [quechua - yupay/to count/ + na’the thing that counts], and how elegant khipus were at expressing “accounts” of information.

In his 1912 paper, Locke laid out the basic foundation of “quipu” “signs”. I quote:

- These knots were used purely for numerical purposes.

- Distances from the main cord were used roughly to locate the orders (as in orders of magnitude, ones, tens, hundreds, etc. ), which were on a decimal scale.

- The quipu was not used for counting or calculating but for record keeping. The mode of tying the knots was not adapted to counting, and there was no need of its use for such a purpose, as the Quechua language contained a complete and adequate system of numeration.

- Other specimens examined contain the same types of knots there being but ten variations in all, two forms for the single knot and eight long knots. These eight differ from each other and from the single knot only in the number of turns taken in tying. There is nothing about any specimen examined to give the slightest suggesion that it was used for any other than numerical purposes.

- If the hypothesis that this quipu is a record of the same classes of objects be correct, it would seem to indicate the colors in this case have no special significance, but were taken according to the fancy or convenience of the maker. This does not signify that there was not a rough color scheme in sue for some purposes.

- These specimens confirm in a remarkable way the accuracy with which [the Inca] Garcilasso [de la Vega] described the manners and customs of his people.”

Locke named the main cord, from which the knotted cords are attached, the “primary” cord. He noted that some cords seemed to be “top cords” and some were “pendant” cords, and some were subsidiary cords attached to either top cords or pendant cords. By reading the knots on a top cord and realizing that they were the sums of the cords in their adjacent cluster, he surmised that they used base 10, and that cords were read, bottom up, as 1s, 10s, 100s, etc. These positions on the cord could be read horizontally as a “register (order in Locke’s words)”, with all the 1’s lining up, 10s, etc (an especially elegant display of knotting skill). The digits 1 through 9, were represented as a series of single knots, or a long knot, or another specialty type of knot. 0 was representd by the absence of a knot in that position. This realization, that quipus encode numbers as knots, and colors encoded categories was the essential breakthrough to begin the decipherment of the quipu gene.

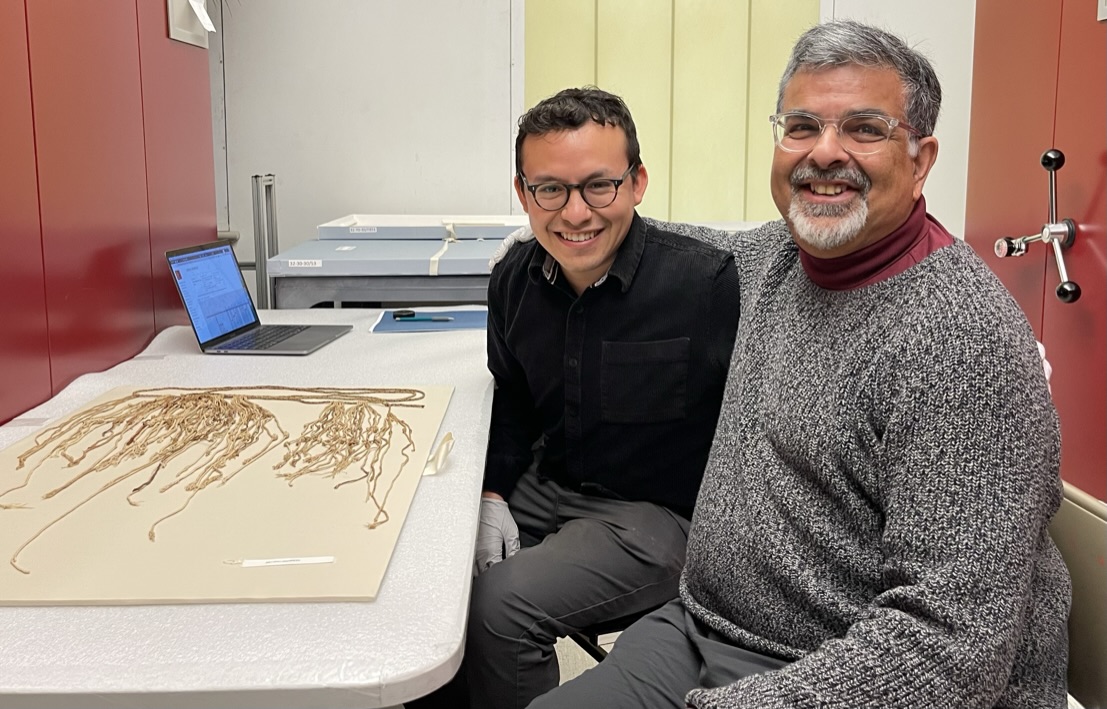

The next phase of khipu history is superbly described by my friend Manuel Medrano, in his wonderful [Quipu Biography].

“The fact that Inca-style quipus remain largely undeciphered is probably the most alluring aspectof the field, though tangible progress remains challenging. The only undisputed decipherment,that of base-10 numerical knots, was achieved in the early twentieth century (see Locke1912 under Quipu Collecting and Early Research and Locke 1923 under Quipu Conventions). Since then, efforts to decipher quipus’ other (non)numerical properties have increasingly incorporated ethnographic analogy (the use of comparative anthropological data to interpret the archaeological record) and data science. Among the most concrete achievements in this regard appears in Hyland 2016 and Clindaniel 2019. Hyland describes how, in the labor accounting quipus of a 20th-century village, bands of same-colored cords registered individual level data, while repeating sequences of colors recorded aggregate data. It is proposed by analogy that ancient quipus could have functioned similarly. Chapter 5 of Clindaniel’s work statistically corroborates this hypothesis (among others of Hyland’s) across the six-hundred- plus samples in the Open Khipu Repository (OKR), offering a valuable clue regarding Inca quipu semiosis. Exploratory computational surveys have also been carried out by both Clindaniel and Carrie Brezine. The demonstration in Clindaniel and Urton 2017 of symmetries in knot directionality across the Pachacamac quipu corpus leads the authors to argue for a significant degree of conventionalization in pre-Hispanic quipu signs. Brezine’s analyses, published in Urton 2005 and Urton and Brezine 2011, enabled the identification of quipus with closely matching numerical sequences, as well as the mathematical clustering of myriad samples using a method borrowed from phylogenetics. A potentially more direct route to understanding ancient quipu conventions would be the identification of surviving specimens and colonial documents that record the same (or same type of) information. Medrano and Urton 2018 elaborates on one such provisional match, describing how the names and social groupings of tribute payers involved in a 17th-century administrative survey may have been registered on six quipus reportedly from the same area. Urton 2006 presents a quantitative analysis by Carrie Brezine that finds dozens of potential “census quipus” in the OKR with numerical distributionsthat are statistically similar to those of colonial-era census documents. Other approaches remain exceedingly conjectural…”

As a high-school student, in a National Science Foundation summer math camp at UC Berkeley, I discovered mathematician Marcia Ascher and anthropologist Robert Ascher’s book on khipu (Code of the Khipu) in a college bookstore. Much of the Ascher’s research was synthesized in the detailed measurement of over 200 khipu, coupled with an extensive mathematical analysis, done by hand, and a very quick mind, of every khipu in that collection. This groundbreaking work, known as the Ascher databooks, serves as the foundation for my research with Manuel Medrano. Later in our journey, we will return to it. Now, there is a new generation of scholars analyzing khipu who are mathematically literate, and are using data science techniques to analyze the khipu. These include two graduate students from Harvard - Jon Clindaniel, who discovered the statistical difference in cord values between banded khipus and seriated khipus, and Manuel Medrano, who deciphered the first “Rosetta Stone” khipus - using a Spanish census document that matched several khipus collected from the Santa Ana Valley.

In the vocabulary of language decipherment (palaeography), Locke discovered signs (knots) and how they worked. Sabine Hyland, and others, increased the vocabulary of signs. Ascher explored ways that the signs interacted mathematically. Now, with today’s tools of a 650+ khipu database built in the Khipu Field Guide, and the statistical power of modern day computing, it’s time to build on the scaffolding provided by these dedicated scholars.

Describing a Khipu

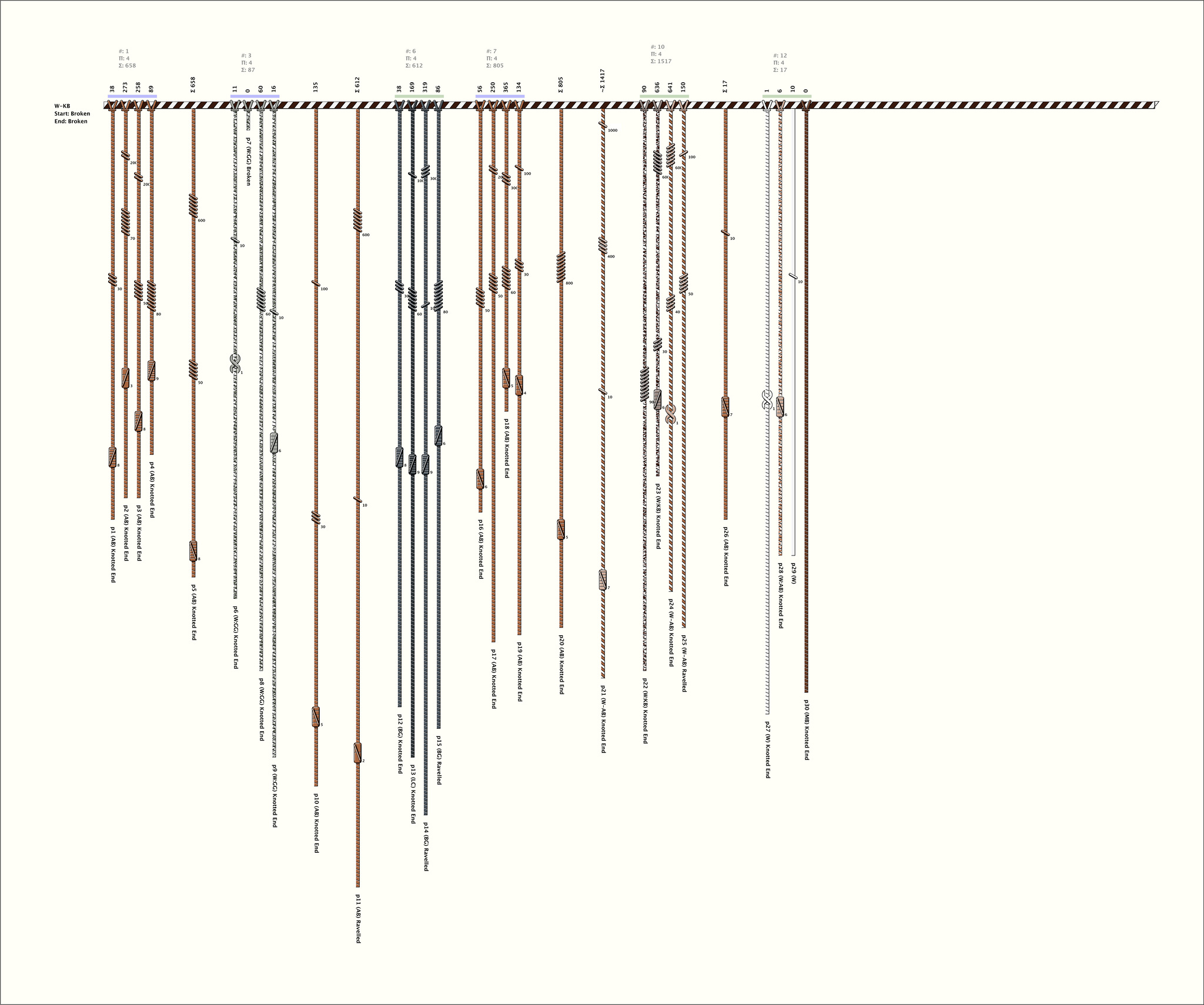

How do you read a khipu? Think of each cell in a spreadsheet as a knotted cord, where the knots represent the value of the cell. Then think of each group of cords and subsidiary cords as a row or column. Knots represent some of the information, but additional information is represented by the cord itself - it’s color for example. This color information is clearly important (view all the white cords in the above khipu for example), but the symbolic meaning of the colors has been lost. Additional encoding information is represented in the way the knot is tied, the way the cord is attached to the primary cord, the ply/twist of the cord, etc…

A khipu is made of thin pendant cords wrapped around a primary cord. The cords hanging from the primary cord can go up (known as a top cord) or down (known as a pendant cord). Cords can be attached to pendant cords as subsidiary cords (for example yearly totals might have four quarterly totals subsidiaries). They can have a twist in the cords making (known as an S twist or a Z twist depending on the axis of the twist i.e. a / direction is a Z twist, and a direction is an S twist. The cords can be attached onto the primary cord in one of two fashions, away from the viewer Verso, or towards the viewer, Recto.

Usually the primary cord has some indication of beginning and end. The beginning was often attached to a tufted ball of thread, called a kayte. Sabine Hyland has postulated that kayte categorized the type of khipu, based on their thread colors. The other end, known as the dangle, simply had a long dangling end! Like headless statues, most of the primary cords kayte are missing, and so that data is missing from the Khipu Field Guide.

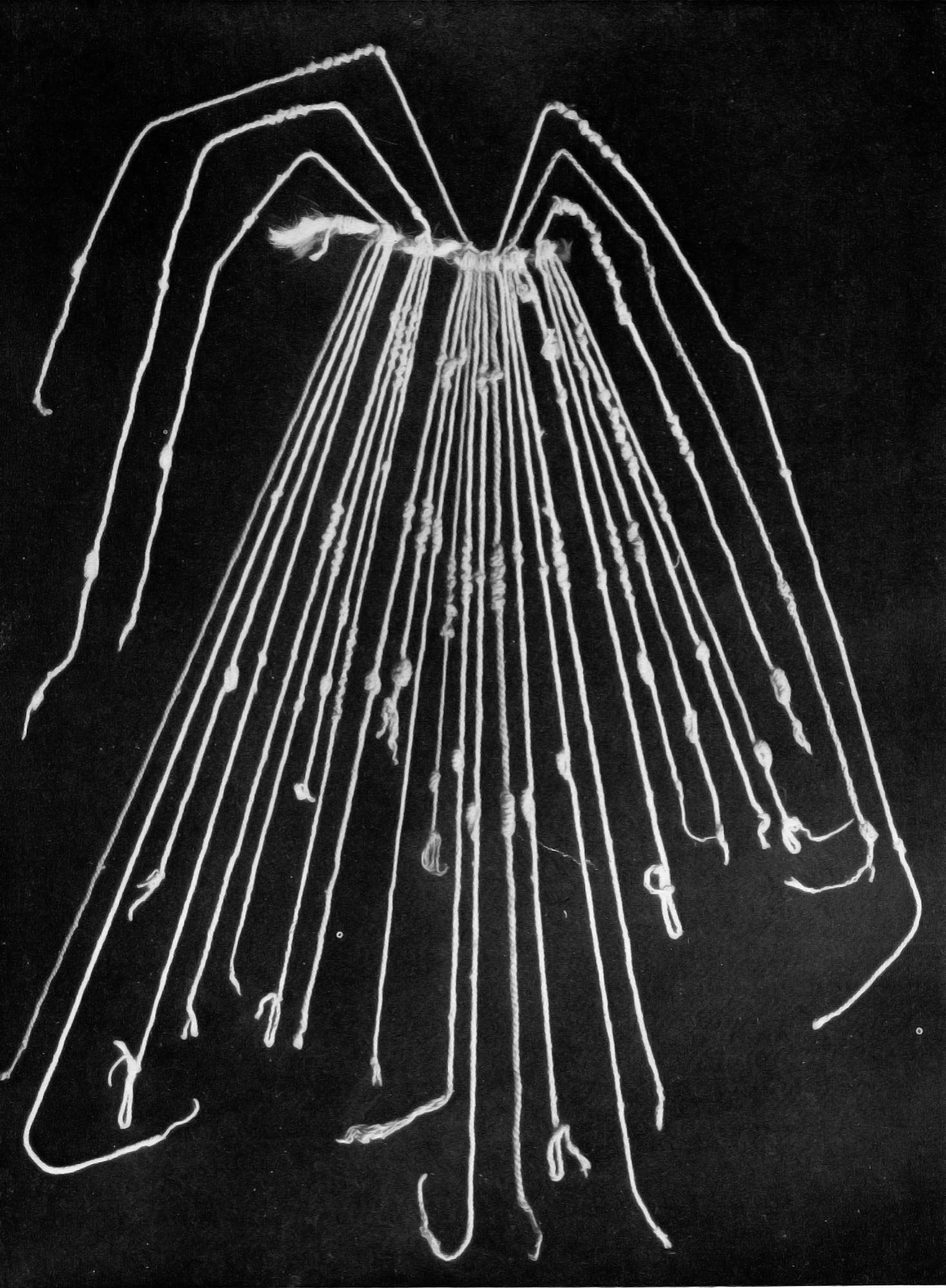

The cords are knotted in various forms and twists to indicate …something … usually numbers. We’ll go into that more later. Cords can have colors, including mixed braided colors. In the topmost picture you can see a large khipu, with a primary cord, many pendant cords, some with subsidiary cords, and cords of many colors. Below is one of Leland Locke’s canonical khipus described in 1923 that started khipu studies in the modern age. First, 1) a photo, followed by 2) a similar drawing, followed by 3) one of my symbolic “renderings” of UR166.

Photo of UR166, first described by Leland Locke in 1923 - Now located in the American Museum of Natural History in New York:

Khipu centerfold of B-8715, by Leland Locke from his book, demonstrating his discovery of a base 10 sums in the khipu by analyzing top cords vs bottom cord sums. This khipu is not presently listed in any database:

Symbolic rendering of UR166 using modern vector-oriented graphics, by the author:

In the symbolic rendering, you can see that certain top cords are the sum of the values of their adjacent pendant cord clusters.

Locke discovered that the Inkas used a base 10 system, by noticing that the value of top cords as a decimal system equaled the sum of a cluster of pendant cords. Along with discovery of the fact they used base 10, he also noticed they had a 0, in this case noted as no-knot present in the cord’s anoted place. (sorry couldn’t resist).

The use of base 10 is interesting. Older Wari (Spanish: Huari) khipus have been found using base 5. One line of reasoning is that for all practical purposes, there is little advantage in base 10 over base 5, unless you like to quarter and half things. Doing 25%, 50% and 75% in base 5 is difficult. It’s easy in base 10, where you have that factor of two built in, so to speak. So if you like to quarter and half things you’re likely to use base 10. The Inka’s were especially found of halving and quartering when categorizing entities. This is especially evident in the categorization of ayllus - the term given to a community of people, similar to the anthropological equivalent of a moiety. For example, a city or village is divided into hanan (upper) and hurin (lower) communities - hanan being Inka ayllus, and hurin being non-Inka communities. Alternatively a city can also be divided into four quarters, for example, the famous word Tawantinsuyu that was the name for the Inka empire Tawa(four)-n(3rd person possessive)-tin(together)-suyo(quarters/countries/states)…- Collasuyo (SouthWest)

- Chinchaysuyo (NorthWest)

- Antisuyo (NorthEast)

- Contisuyo (East)

For another look at how a khipu is constructed, see this wonderful 3D animation in Spanish on Facebook, produced by MALI - the Museo de Arte de Lima, in Lima Peru.

A Khipu Typology

We know (or can infer) that some khipus are census accounts, some have to do with calendars, some to record labor tribute taxes, etc. What does the current research indicate?

Based on her readings from Spanish chronicles, Magdalena Setlak, lists these khipu categories:

- Historical khipus, which contained Inca myths and history, the genealogy of their rulers and the songs that commemorated them.

- Religious khipus, in whose strings huacas [sacred sites], sacrifices and offerings were recorded.

- Calendrical and ceque khipus, recording religious cycles and the social organization of Cuzco, as well as agricultural cycles.

- Judicial khipus, among which we have identified three types of records: codes, files, and testaments.

- Local khipu-registers, containing detailed records of all the inhabitants of each community and district.

- Khipu-censuses, central records maintained by state authorities.

- Khipu-corvee, in which all the services provided as mita or corvee were recorded.

- Tax-khipus, used to record tax obligations and compliance, and which in many cases were combined with khipu-corvee.

- Khipu-accounts, containing all accounting records except those that recorded tribute and mita, such as, for example, the stocks held in storehouses and way stations, and what had been distributed.

- Khipu-maps, composed of place names or the names of ethnic groups, and reflecting, in some cases, Inca conquests during their military campaigns.

- Khipu-letters, the content of which we do not know, although certain references in the chronicles point to their existence.

Data-science investigation of khipus reveals that, there are indeed, roughly about ten “types” of khipu. The challenge is we can only guess what the types are, and therefore, the types may not match the above list!

Nonetheless, with this typology in mind, can we find khipus in the Khipu Field Guide that are examples of these types? The answer is a qualified YES. Calendrical khipus, census khipus, and khipu registers exist that have been positively identified as such. However, historical, religious, judicial, etc., khipus - anything that implies textual accounts, have not been identified either in the textual transcripts of khipus, or in khipus themselves.

Decipherment

Now that you have a basic idea, of what a khipu can be, let’s learn to “read” a khipu.